Amsterdam

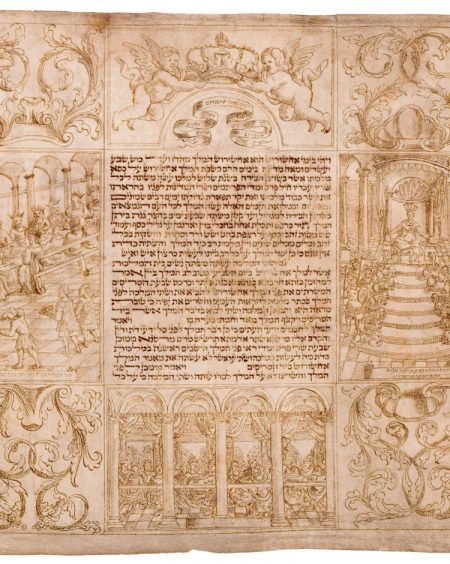

This profusely illustrated Dutch scroll is distinctive for its thirty-eight illustrations delicately drawn in sepia ink. The artist created a rhythmic cadence in this work by surmounting the first text column of each membrane with an arch, inside of which two winged putti raise a crown. The other text columns are surrounded on all four sides by elegant interior and exterior scenes, rendered with masterful use of perspective, which portray events relating to the Esther story.

Within a banderole at the bottom of each illustration the scribe penned a descriptive text. These explanatory words, written in semi-cursive script, are excerpts from the Targum Sheni, an extensive Aramaic paraphrase of and midrashic commentary on the book of Esther. Despite the inclusion of quotes from the Targum Sheni, few images incorporate visual references to its midrashic tales. The first illustration, a depiction of Ahasuerus seated on King Solomon’s throne, does, however, relate to an extensive narrative in the first chapter of the Targum Sheni that describes the splendor of this throne, how the rulers who conquered Jerusalem transferred it to Babylonia, and how it arrived later in Shushan.

This scroll also contains some unusual representations. One is of Mordecai standing in a room with a wall filled with books. He is portrayed as a scholar, perhaps reflecting a rabbinic tradition that informs us of his remarkable knowledge of seventy languag- es. The Talmud relates that his understanding of foreign languages helped him uncover the plot of Bigthan and Teresh against Ahasuerus, an act that led to Mordecai’s eventual recognition and rise in government. Another striking illustration is the depiction of two merrymaking dwarves dancing and playing stringed instruments in celebration of the Jews’ delivery from destruction. The dwarves appear to be based on engravings by the artist Jacques Callot (1592–1635) who created a series in which they were featured as the central subject.

Throughout the scroll, the artist incorporated classical elements, as seen, for example, in the inclusion of classically inspired armor in depictions of Haman and the servants of the king. The decoration of the megillah begins with a triumphal arch reminiscent of Roman triumphal arches constructed for royal festivities throughout Europe from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century.

selected literature Grossfeld 1991; Hanegbi 2001.

Amsterdam, ca. 1675

Parchment, 5 membranes, 1 benediction panel + 13 text columns, 276 × 2270 mm (10.9 × 89.4 in.) Turned wooden roller, 422 mm (16.6 in.)

Braginsky Collection Megillah 17